Galician Wine Basics: Xabre & Sábrego

Galicia’s soils might seem simple, but you can’t take them for granite.

If you’re still with me after that and didn’t throw your device across the room in disgust, you’ve earned my respect. Never fear, that was the last pun for this post—only information from here on out.

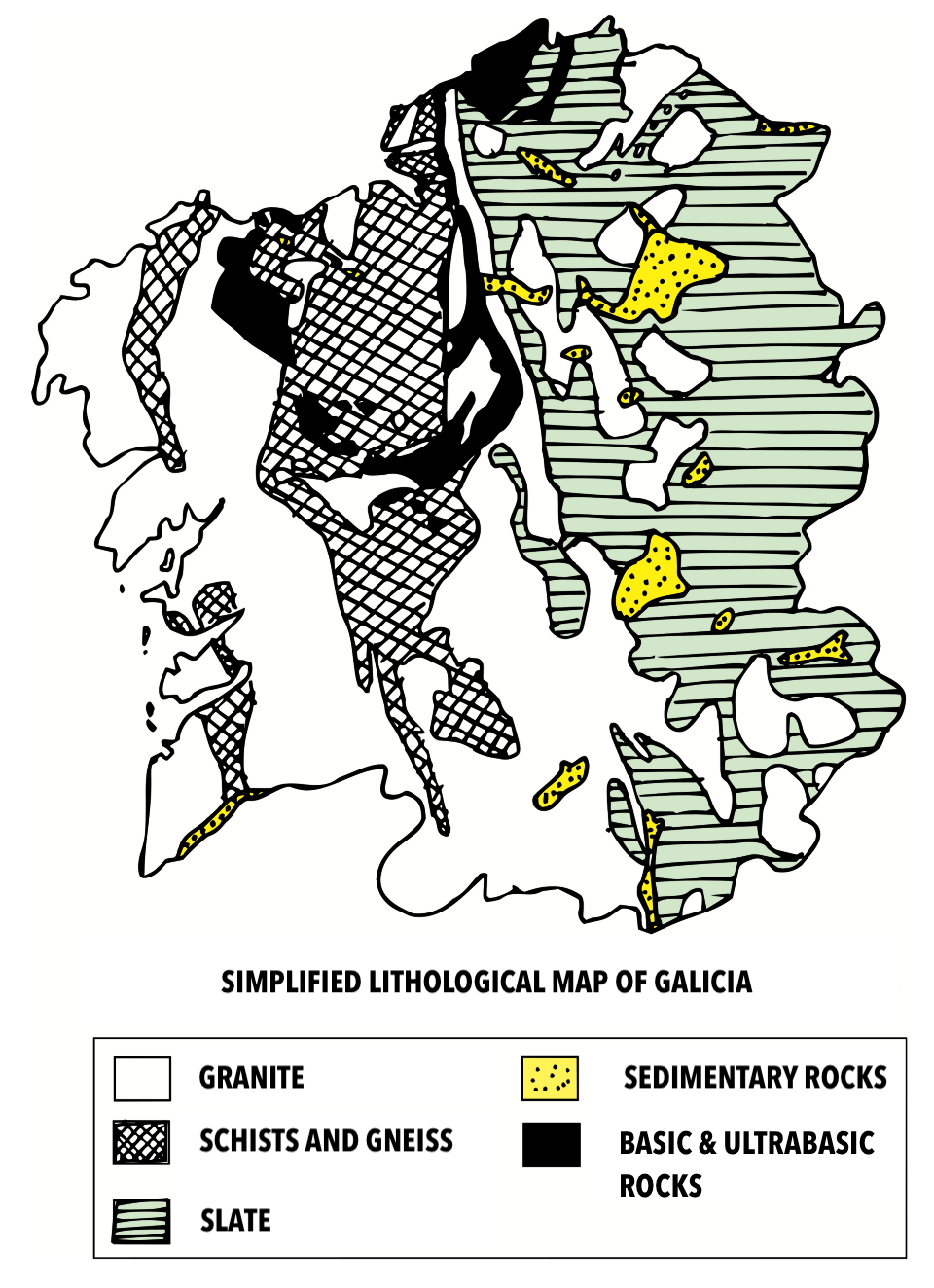

It turns out that in a lot of Galicia, you actually can take the soils for granite, because most of Galicia sits on top of a big hunk of the stuff. The northwest corner of Spain began to take shape about 300 million years ago, when the smaller landmasses that would form Pangea began to collide. The tectonic forces they generated created mountains the height of the Himalayas, in a massive belt that stretched across parts of modern-day Europe, North Africa, and even North America. This mountain building event, whose official name is the Variscan Orogeny, was responsible for creating the western ranges of Portugal and Spain, upon whose foundation Galicia sits today.

Miguelferig, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons (my translations)

If you’ve been to Galicia, you’ll notice that its mountains are decidedly un-Himalayan. Millions of years of erosion has worn down the high Variscan peaks into the short, round mountains that today make up the Galician Massif, a range that extends from central Galicia eastward into Castilla y León. The same erosion eventually exposed the granite that had formed from cooling magma as the plates collided. On the surface, the sedimentary rocks that originally covered Galicia were transformed by heat and pressure into metamorphic rocks, which kept the granite from emerging. Over millions of years, erosion removed the metamorphic layers, unveiling the granite that now makes up the bedrock of much of western Galicia.

This granite is also the base of one of the most important soil types in Galician wine: the sandy, decomposed granite soil known as xabre in Rías Baixas and sábrego in Ribeiro.

This soil forms as solid rock is worn down over a long time by weather and water, eventually crumbling into a loose, sandy material. Decomposition starts when feldspar, one of the minerals that make up granite, changes into a clay mineral called kaolin. Once that clay forms, it allows water to more easily seep into the rock, which weakens it from the inside and makes it easier for it to crack and fall apart. Meanwhile, quartz and mica, the other main minerals in granite, are much more resistant to weathering and tend to stick around in larger grains that give the soils a loose, sandy texture after the rest of the rock has broken down.

Xabre / sábrego is important for grape-growing in Galicia for several reasons. The first is that it drains really well, which is important in a place where it rains all the time. Without the sandy texture of these soils, vine roots would quickly get waterlogged, suffocating them and leading to root damage, rot, and the inability to absorb necessary nutrients.

Xabre takes it to the other extreme: over the course of weathering and soil formation, it loses calcium, magnesium, and potassium, leaving it so nutrient-poor that in order to nourish the vines, the plant’s roots have to go deep. In Rías Baixas, it’s common for vine roots to grow two or three meters underground and spread out closer to the surface in search of nutrients. The low water retention naturally limits vine vigor, keeping the plants healthy and helping balance yield with quality, and the deep rooting allows the soil’s granitic texture to be fully expressed in the wine, in what some people refer to as minerality (I’m only repeating what winemakers have told me, don’t send the minerality police after me!).

The minerals left over after the granite decomposes also help regulate the ripening cycle. Quartz and mica absorb and reflect the sun’s rays during the day, which helps grapes accumulate sugar. At night, the soil cools quickly, preserving acidity. This combination of warmth during the day and freshness at night allows for grapes to be ripe and flavorful but still fresh and vibrant. All of these factors make xabre / sábrego especially suited for making aromatic white wines.

Is xabre / sábrego an advantage across the board? In typical Galician fashion, it depends. In dry, hot areas, the vines are too stressed, acidity can drop too much, and alcohol can spike, which throws the wines out of balance. But in regions with Atlantic influence, mild temperatures, and enough rainfall, it can put just enough stress on the vine to create the wines from Galicia that we know and love.