Yes, Virginia, There Are Red Wines in Galicia

The first summer I came back to the States after moving to Galicia, I was in a decently sized northeastern city and decided to kill some time by going wine shopping. I walked around the store, which Google had told me was the number one shop around, and checked out the ample stock of Burgundies and Bordeauxs, Sancerres and Sangioveses, wines from California, Oregon, Washington, South Africa…

As is usual in American wine retail, the Spain section was about a quarter of the size of the rest of the sections. Still, there were a decent number of Riojas, a few Albariños I recognized despite not having begun my spiral into complete Galician obsession, and even a couple of wines from Bierzo.

But something was missing. So I asked the guy at the help desk: “do you have any red wines from Galicia?”

He returned the question with a puzzled look and said, “they don’t make red wines in Galicia.”

Fast forward to today, and the answer would still be the same. It’s not just an American problem. No matter what country you’re in, we don’t drink nearly as much red wine from Galicia as we should—because most people don’t know that red wine from Galicia even exists.

So, *climbs up on soapbox*: they do make red wines in Galicia, they are available in the export market, and you have no excuse not to drink more of them, damnit!!

Galician Reds - A Primer

I’ve written a longer exploration below along with some recommendations, but for your own personal edification I’ll drop in the basics:

What they’re made from: Mencía, the various Caíños (Tinto, Bravo, Longo, etc…), Brancellao, Merenzao (aka Trousseau) Sousón, and Espadeiro, though the list doesn’t end there.

Where they’re made: All of Galicia’s denominaciones de origen produce some amount of red wine, but the powerhouses are Ribeira Sacra, Ribeiro, and Monterrei, with a smattering of reds in Valdeorras and Rías Baixas.

What styles they make: Galicia has a long tradition of drinking young red wines, and it’s still very typical to see oceans of young Mencía on offer alongside wines from Rioja and Ribera in taverns wherever you go. Nowadays, it’s also common to see barrel-aged wines, although there’s no age classifications of “Crianza” or “Reserva” . New oak isn’t very common, as it tends to overpower the traditional Galician grapes, which lean delicate. That means barrel aging is done in mostly large, old wood.

What You Should Drink — If You Like…

Cabernet Franc

Try: Mencía

Red cherry, raspberry, violet, herbs, mineral

Medium body, medium acidity, moderate tannins

Schiava

Try: Caíño Tinto

Cranberry, redcurrant, floral notes, black pepper

Light to medium body, high acidity, firm tannins

Gamay

Try: Brancellao

Red plum, sour cherry, spice, slate

Light to medium body, soft tannins, bright acidity

Cool-Climate Syrah

Try: Sousón

Blackberry, black cherry, smoke, spice, earth

Fuller body, deep color, higher tannins

Blaufränkisch

Try: Espadeiro

Pomegranate, cranberry, wild herbs, saline note

Very light-bodied, crisp acidity

Trousseau

Try: Merenzao (it’s the same grape!)

Rose petals, red and black berries, spice, earthy notes

Light to medium body, medium tannins

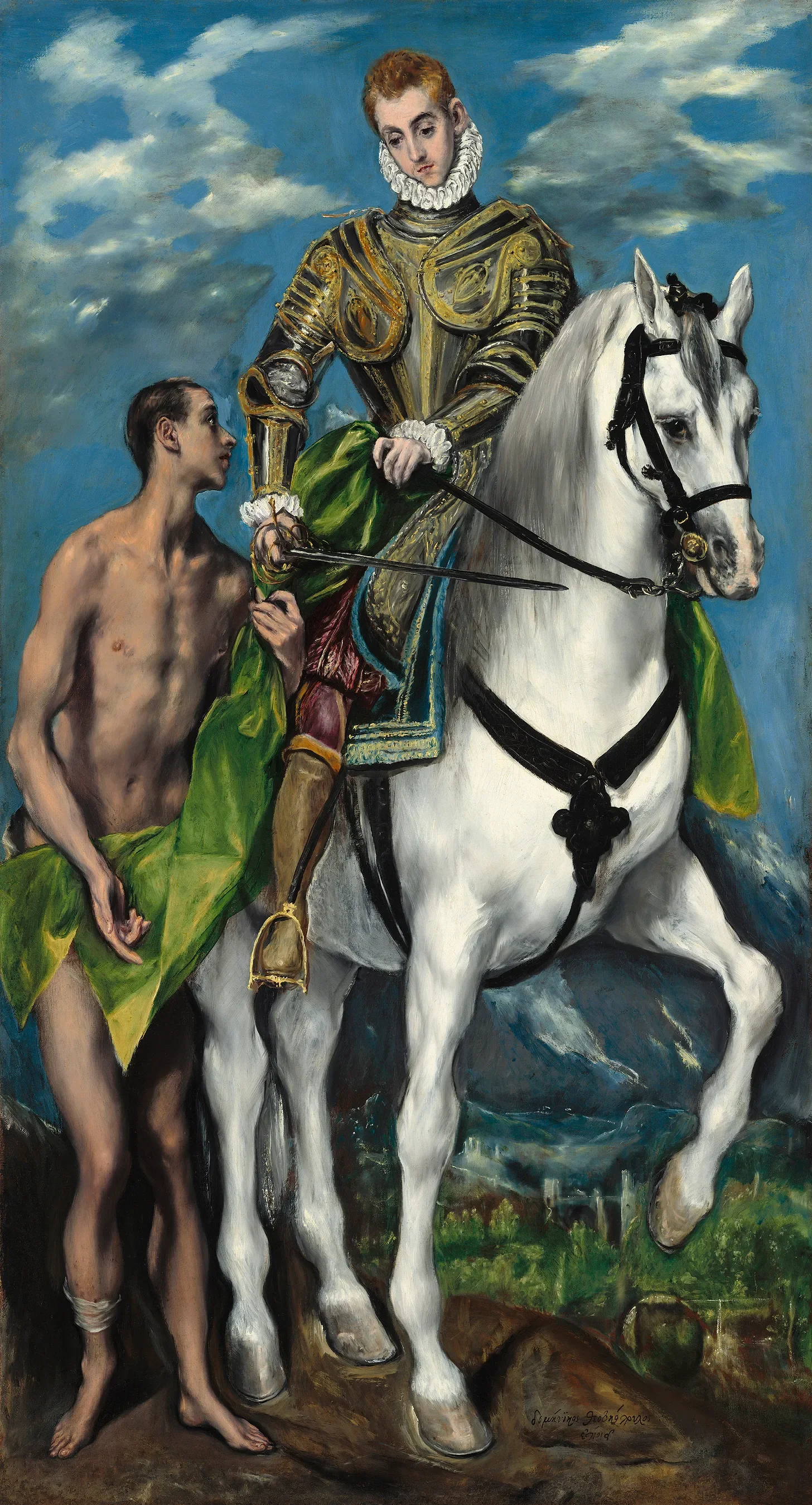

“Polo San Martiño, deixa a auga e bebe o viño”

The issues with Galician reds are ongoing, but I’m inspired to write about them now because November 11 was the feast of San Martiño, or “little St. Martin”, as Martin of Tours is known in Galicia. In the traditional Galician calendar, San Martiño marks a time of preparation for the oncoming cold of winter—appropriate for a celebration of the saint who cut his cloak in half to share it with a poor man shivering in the cold. Around San Martiño, families would slaughter a pig and preserve every part of its meat to feed themselves throughout the coming year.

San Martiño’s importance in the Galician calendar is reflected in a litany of sayings like:

“A cada cochinillo lle chega o seu San Martiño” (“Every pig has its Saint Martin”)

“Polo San Martiño deixa a auga e bebe o viño” (On St. Martin’s Day, swap water for wine)

“En San Martiño, mata o teu porco e bebe o teu viño” (“On Saint Martin’s Day, kill your pig and drink your wine”).

I’m never one to pass on seasonal cheer, but I’m going to limit myself to the latter activity. My landlord probably wouldn’t be on board with the whole pig slaughtering thing, and anyway, once you’ve killed it, where are you supposed to hang it in a one-bedroom apartment?

So, in keeping with tradition, I will be drinking viño tinto. But beyond that, I want to highlight Galician red wines because I think they work especially well for this late fall, not-quite-yet-winter time we’re in right now. You might not want to sink into the warm embrace of something with 15% ABV just yet, but you’re ready to leave the chilled whites and rosés behind.

Fresh, Atlantic-tinged red wines from Galicia make a perfect midpoint in our journey towards heartier fare. They straddle the seasons, carrying the memory of summer trips to the fruit stand while looking forward to the chill of year’s end. They’re the closest approximation to the idea I have in my head of fall. The air changes, the temperature and humidity drop, it gets… crisp.

Maybe that’s where the mental link comes from; when I taste red wine from Galicia I immediately go to descriptors like “crisp” or “crunchy.” These concepts get thrown around a lot in modern wine parlance—they’ve become mainstream enough that Wine Enthusiast has even weighed in defining crunchy wine as “crisp and taut…with a fresh cranberry-like tang.”

This crispy-crunchy fall feeling I get from Galician reds is the sum total of their structure more than any one sensation: the tannins are a bit rustic and wild, the acid is tangy, and the fruit is just beginning to be ripe, like biting into a firm plum that could really do with a couple more days out on the kitchen counter.

These are enormously pleasurable wines to drink, but we don’t drink nearly as many of them as we should—partly because they’re still so under the radar, and partly because they’re not everywhere. At the same time, that scarcity only makes the prospect of finding and enjoying them more thrilling. Their limited appearances on shelves and wine lists means that when you do encounter one in the wild it’s like you’re in on a secret that the rest of the wine world is too busy to notice. And once you’ve tasted enough of them, and they’re in the regular rotation, their value becomes obvious. You realize that these wines aren’t just for geeks or “somm candy”, but immensely drinkable, real wines.

What would help Galicia’s red wine-producing regions the most is a shift in our collective mindset: actively looking for these wines, seeking them out in restaurants and at independent retailers, and keeping them in your glass all year round.