Valdeorras: Reviving the Valley of Godello

Valdeorras is Galicia’s second-oldest Denominación de Origen, but its winemaking tradition stretches back to Roman times. Its modern story mirrors the other wine regions in Galicia: it’s the story of a few determined individuals whose hard work managed to pull a wine region back from the brink of extinction and raise it to international status.

This valley that forms a natural entry point into Galicia has been populated for thousands of years. Bronze-age petroglyphs hint at pre-Roman culture, but the castros, pre-Roman hill forts, are the most obvious legacy of the people that first inhabited Valdeorras. From their perch high above the valley, the people in these hill forts could probably have seen the distant dust cloud growing larger as it approached them, and spotted the glint of sunlight from armor and swords. Maybe they even saw a standard waving in the wind or heard the trudge of marching feet. Castro culture was soon brought down to earth with the arrival of a different people, replete with armor, chariots, and a whole lot of thirsty legionaries.

Valdeorras’ story mirrors that of the Romans in ancient Hispania. The valley was an ideal area for the burgeoning empire to settle: it was smack in the middle of an important road between capitals, and also had fertile soils perfect for planting vines–especially important for the Roman army, whose legions guzzled down 12,000 liters of wine a day. But it wasn’t only viticulture that led the Romans to settle in Valdeorras. They were hungry for gold, and they would stop at nothing to dig it out of the mountains rising up in front of them.

"Tunel de Montefurado" by José Antonio Gil Martínez is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Roman hunger for gold spawned the most pervasive legend about Valdeorras’ name. Both the reddish earth of the valley and the Roman’s mining exploits gave rise to the idea that Valdeorras means “Valley of Gold.” It does sound right: (Val= valley, orras = aurum), but it’s just too good to be true. Like ancient Gallaecia, Valdeorras’ name comes from the people who were living there when the Romans rolled into town.

Unlike other places where the Romans and the locals didn’t exactly get along, in Valdeorras the native Gigurri were integrated into Roman life and customs almost immediately. They even applied their name to the region’s capital, the Forum Gigurrorum, and one Gigurro was even made a commander in the army. Today, you can read about Lucio Pompeyo Reburro Fabro on his white marble tombstone dating from the 2nd or 3rd century and located in front of the church of San Estevo in A Rúa.

“After the fall of the Roman empire, the term gigurro went through some changes, evolving into giorres, eurres and iorres. By the end of the Middle Ages, the name was already Val de Iorres, which finally came to rest as Valdeorras.”

“Dedicated to Lucio Pompeyo Reburro Fabro, son of Lucio, belonging to the Gigurri, from the Pomptina tribe and native of the Calubriga castro, assigned to the Praetorian VII Cohort, beneficiary of the tribune, treasurer of his century, standard bearer in his century, prosecutor of the treasury, decorated with commiculus by the tribune, chosen by the emperor himself.“

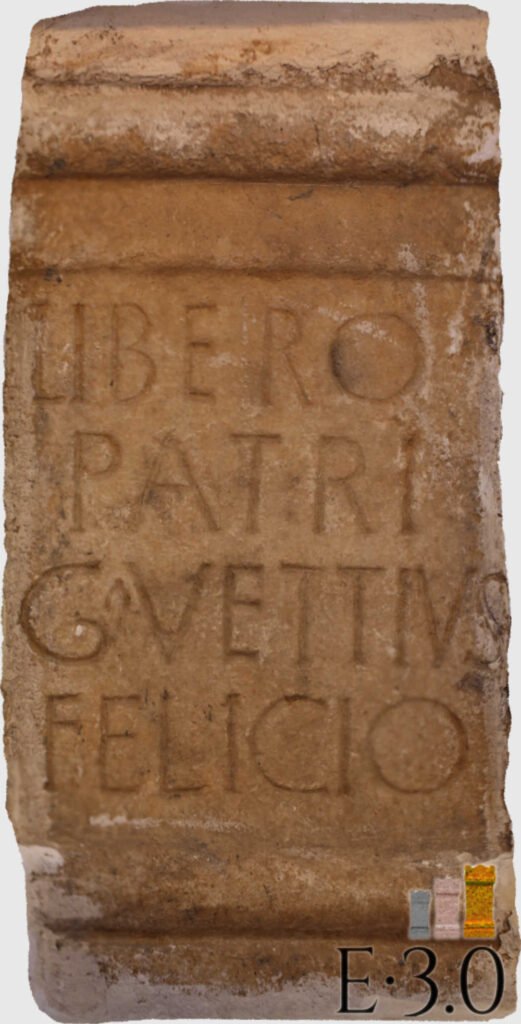

“Libero Patri/ Gaius Vettius/ Felicio”

(Gayo Vettius Felicio had this altar erected to Liber Pater). ”

Not only a god of wine—he later became Bacchus—Liber Pater was also the god of viticulture, male fertility, and freedom. It could be that Gayo Vettio built this altar because of his trade, and that he was the first known wine grower or wine seller in Valdeorras.

After the fall of the Roman empire, northwestern Spain came under the rule of the Suevians and the Visigoths, and eventually the Moorish kingdoms who invaded in the 8th century. The Christian reconquest brought monasteries and churches established by orders like the Benedictines, some of whom owned land in Valdeorras and made wine. In the year 940, a document donating land to the monastery of San Martín de Castañeda references: “terra vel vineas que sunt in Iorres.” That is, the document lists some “vineyards that are in Iorres.” Viticulture would only continue to expand.

From the late medieval period on, Valdeorras became a football passed between successive kingdoms. Galicia, Asturias, and León all laid claim to the territory at one point or other, all under the watchful eye of a parade of counts and lords. Like most of medieval Galicia, wine was a commodity used by growers to pay rent to monasteries and nobles, and later to make a little money for daily needs. By the end of the 15th century, wine was often the only source of income people had, and by the 18th century nearly every town in Valdeorras was surrounded by vines—from the Sil river valley to the Bibei, home to one of Valdeorras’ great architectural treasures.

“The Sanctuary of A Nosa Señora das Ermidas (Our Lady of the Hermitages) is one of the best examples of Galician baroque architecture. Completed in 1726, it’s located to the south of Valdeorras, where the Bibei valley curves and turns toward the Ribeira Sacra.

For centuries, the Sanctuary formed an important part of the viticultural scenery of Valdeorras. Terraces, now mostly abandoned, once covered the slopes surrounding the sanctuary and over 200 individual plots were farmed.”

Although we’re left with traces of Roman mining, where wine is concerned things become a bit murkier. The two pieces of evidence that can help us get on the trail of the first vines are literally written in stone. The first is an altar inscription that mentions a Roman by the name of Gayo Vettio Felicio. His altar was dedicated to the original Roman god of wine, Liber Pater, and it’s preserved in the church of Santurxo in O Barco.

The 19th Century

The 19th century began with bloodshed when Napoleon’s French troops passed through during their invasion of the Iberian Peninsula. Since Valdeorras was the gateway between Galicia and Castilla-León, it was particularly hard hit with French aggression, culminating in the French general threatening to burn down the church at As Ermidas. Luckily, he didn’t follow through on his threat.

In 1882, another disaster struck when phylloxera invaded, destroying over a thousand hectares in just a few years. A Valdeorrés named José Núñez discovered that the best way to stop the plague was by uprooting the infected vines and burning all the contaminated organic material, replanting vines using American rootstock. After years of work, Valdeorras’ vineyards regained their scope, but not their former glory. The story was the same as in the rest of Galicia, and traditional varieties like godello and brancellao found themselves replaced by mencía, garnacha tintorera, and palomino.

Revival: Bringing Valdeorras into the 21st Century

The arrival of the railroad in 1883 meant that Valdeorras’ wines could now travel to the rest of Galicia. Oceans of bulk wine departed for A Coruña, Santiago, Lugo and Ourense, where they were eagerly drunk in taverns and restaurants. Palomino and garnacha tintorera were valued for their easy drinking and deep color, and they continued as majority grapes for most of the 20th century. This echoed the rest of Galicia, as locals tried to eke out a living selling wine and focusing on quantity over quality.

In 1945, the Denominación de Origin Valdeorras was born, making it Galicia’s second official wine appellation after Ribeiro. The Ministry of Agriculture’s decree protected the “Valdeorras ” name, and in 1957 established its approved white grapes as “jerez” (palomino) and godello, and red grapes as garnacha, alicante, mencía and gran negro. The newly-formed wine region catapulted it into another league of increased demand, which in turn led to the first cooperative wineries. The Cooperativa de Jesús Nazareno in O Barco, Cooperativa de la Virgen de las Viñas in A Rúa and the Santa María de los Remedios co-op in Larouco all helped to modernize production and help growers get a decent price for their grapes.

"The Cooperative Winery Jesús Nazareno undergoing expansion" -La Region, September 1967

But despite their ability to sell, the cooperatives were still concerned more with quantity over quality. The vast majority of Valdeorras’ wine was still shipped off in bulk, with little regard for separating different grape varieties. Add to that a rapidly aging population, the low profitability of farms, and the tempting alternative of jobs in the slate mines, and we can understand the serious situation Horacio Fernández Presa faced as the head of Agricultural Extension in the early 1970s.

How to save the valley and its vineyards?

It was time to take another step towards quality, through a project that contained its mission statement in its name: ReViVal: Restructuring the Vineyards of Valdeorras. Beginning in 1974, with the help of Luis Hidalgo, José Luis Bartolome, and other Agricultural Extension workers, Fernández would conduct a survey of the growers themselves in order to better understand what varieties could work best in future Valdeorras vineyards.

The winner, by far, was godello.

Between 1975 and 1976, Agricultural Extension workers set about planting new godello vines, and finally collected a tiny first harvest of 4,000 kilos. Over the next decades, they took on the immense work of completely replacing the old vines of palomino and garnacha tintorera with mostly mencía and godello, until in the 21st century Valdeorras is known for producing some of the most exciting single-variety Godello wines in Galicia.

The Revival program has been fighting to recover traditional grapes for 14 years - La Region, 1987

Valdeorras in the 21st Century

Valdeorras now has 1,113 hectares of vines, 1,042 growers, and 43 wineries. Production hovers around 3.6 million liters of wine, of which only 13% leaves Spain. The vast majority of this is white wine, usually single-variety Godello. Valdeorras’ biggest export customers include the US and UK, the Netherlands, and Germany.

The potential of Valdeorras Godello has attracted attention from superstar Riojano winemakers Rafael Palacios and Telmo Rodriguez, who make some of the most sought-after wines from Valdeorras—Palacios’ “Sorte O Soro” was the first Galician wine to receive 100 points from Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate. Wine importer Jorge Ordoñez’s “Avancia” has been crossing the Atlantic to the United States since 2007, and winery groups like CVNE and Pago de los Capellanes also have projects in Valdeorras. It’s clear that the attraction of all these major players lies in the unique terroir of Valdeorras and its expression in its number-one grape, Godello.