Granite & Chestnut & Clay, oh my!

The new (old) materials making their mark on Galician wine.

A return to tradition. Experimentation. The natural evolution of things. Whatever the reason, stainless steel and oak are no longer the only materials you’ll find in Galician wineries. Brought up in the modern era of winemaking, with unprecedented access to knowledge and tools from all over the world, a new generation of winemakers is challenging established norms through their use of unorthodox materials, forcing a reckoning of what Galician wine can—and should—look like.

“Tradition” is a tricky word in the wine business. We talk about traditional grapes, ancestral winemaking methods, and practices in the vineyard that have been passed down through the generations. But how long do people need to do something before we call it a tradition, and what happens when winemakers change things up?

Until about fifty years ago, Galician winemaking tradition dictated pressing grapes in wooden or stone presses and fermenting them in chestnut barrels or cement tanks. In his book “Os Viños de Galicia” (I have the third edition, published in 1981), Xosé Posada writes that although Galician growers lovingly cared for their grapes in the vineyard, winery hygiene was abysmal. Old-timers preferred to rely more on the “if it worked for my father and grandfather, then it’ll work for me” method than avail themselves of modern advances in winemaking.

“A traditional winery in Ribeiro”, published in “O Viño” (1993, Ir Indo Ediciones)In the 1980s, stainless steel came on the scene, ushering Galicia into a new era of cleanliness and control and breaking with centuries of tradition in the cellar. Over time, its use in the winery has become almost sacrosanct as Galicia has developed a reputation for making young, fresh white wines. More premium reds and whites see oak aging, but that’s also a relatively recent convention.

“An industrial winery in Ribeiro”, published in “O Viño” (1993, Ir Indo Ediciones)All this change in the span of just a few decades means that there’s room to reinterpret what constitutes tradition, and a little more experimentation isn’t out of the question.

“Logically, when years go by, something that repeats over time ends up being a tradition,” says Silvia Prieto, one half of the Rías Baixas winery Nanclares y Prieto. “But I don’t think it’s good to settle, right? Otherwise we wouldn’t evolve.”

That refusal to settle has led some winemakers to revisit their history, blending it with contemporary materials to shape a vision of Galician wine in which stainless steel and oak share real estate with chestnut barrels, amphorae, concrete eggs, and granite tanks. In their eyes, these vessels are the best tools to translate Galicia and its grapes to the modern drinker, while making wines that are true to their terroir and honor their past.

Clay

When he began making wine in 1997, Alberto Nanclares worked mainly with stainless steel, as was common at the time—Silvia calls it “the revolution of the ‘80s and ‘90s.” But when Silvia arrived in 2015, Alberto had already started introducing used oak barrels, making sure they wouldn’t mark the wine too much and obscure varietal characteristics.

Soon after, Alberto and Silvia started working with clay. “At first, we weren’t very much in favor of amphorae,” Silvia tells me. “Although there’s clay in Rías Baixas, and there were telleiras [tile-making factories], wine was never traditionally made in amphorae here.” But after conversations with Iago Garrido, who was making wine in amphora at his winery Augalevada in Ribeiro, they decided to give it a try.

The result, ‘Anfora Vermella’, is made from 100% Caiño Tinto. After foot-stomping the grapes, they macerate them on the skins and stems before a 21-day fermentation. Then the juice is pressed into amphorae, where it rests on the lees for 11 months.

Nanclares y Prieto’s three amphorae were made by now-retired master potter Juan Padilla, who supplied clay vessels made at his workshop in Castilla-La Mancha to wineries such as Foradori, Azienda Agricola COS, Frank Cornelissen, and closer to home, Galician winemaker Nacho González of La Perdida in Valdeorras.

“What’s really good about amphorae is how they work as a fermenter,” says Nacho. “I don’t do temperature-controlled fermentations, and if you ferment in amphorae they stay very cool. They’re like gigantic clay water jugs—they regulate what’s inside with what’s outside, so if what’s inside is warmer than the outside clay, it draws that heat outward.”

Nacho González checks on Palomino for ‘Malas Uvas’ before bottling, 2022. Photo by Noah Chichester.The fact that no two amphorae are the same affects how wines behave during aging. In general, a wine raised in amphora is exposed to more oxygen than a wine in a barrel, but there’s a lot of room for variation. “The clay composition varies, and we notice differences: the first amphora is the most porous and my favorite,” Silvia says. “But in general you notice right away that the wines are more evolved from the greater oxygenation the amphora gives them.”

Different varieties also respond better in amphora, a fact Nacho learned the hard way. “In 2023 I put Godello from the same vineyard in two amphorae on the same day,” he says. “One was amazing, but the other had a lot of volatile acidity.”

He’s learned to take fewer risks, he says. “If I ferment in amphora and transfer the wine to barrel before fermentation finishes, I don’t have those problems. That doesn’t happen to me with Palomino, because it forms flor really quickly, so I keep working with Palomino in amphorae and I do less and less with Godello.

His Palomino bottling, ‘Malas Uvas’, or ‘Bad Grapes’, is a tongue-in-cheek rebuke to the Valdeorras D.O. During the quality revolution of the 1980s and ‘90s, “anything that wasn’t Godello was frowned upon, and they recommended uprooting Palomino to be replaced with Godello,” Nahco says. He destems and presses the grapes, and then ferments the must in amphora, followed by 6 months of aging before bottling. “Clay gives Palomino a complexity that I can’t achieve with any other material,” he says.

For Nanclares y Prieto, the initial worry wasn’t too much acidity, but too little. “We don’t intervene at all—we don’t add wax or coat our amphorae,” Silvia says. This is different from other regions where amphorae are coated to prevent excessive acidity loss. When must goes directly into an uncoated amphora, acidity can drop by as much as 1.5 g/L, Silvia explains.

“In our case, since we’re lucky to work with varieties that have naturally high acidity, we don’t coat them. We always choose the vineyard with the highest acidity and the results are very positive,” she says. Although she admits there are better and worse years, Silvia tells me they’re very happy with how their experiment turned out.

Amphorae made by Juan Padilla in Nanclares y Prieto’s winery. Photo courtesy Silvia Prieto.Concrete

At Lagar de Costa, a three-minute drive away from Nanclares y Prieto, Sonia Costa has also spent the last few years thinking about porosity.

“It was a bit of a whim, really,” Sonia says. While visiting a winemaker friend in Rioja a decade ago, she saw a concrete egg for the first time. “I tasted the Viura he was making in the egg, and I was amazed,” she recalls. “I thought, ‘I don’t know what this is, but I want one in Cambados.’”

But when she applied for a government grant to finance the concrete egg, things got more complicated. “The people from the Galician government called asking how on earth this woman was going to spend so much money on a concrete tank, since concrete was kind of pigeonholed as something for making low-quality wines,” she says. “So we explained that it was for aging, to try to make albariño from a different angle, achieve higher quality, sell it at a higher price, etc.”

With the government convinced, they bought the egg. “We almost had to take the roof off because it wouldn’t fit,” Sonia laughs. “It was a drama—there was some collateral damage getting it inside.”

A concrete egg, ready to go into the winery. Photo from their Instagram.“We put the wine in the egg, it stayed there for a year, and we tasted it every couple of months,” Sonia says. “At first I was worried it might alter things, since Viura has one pH and Albariño has another. I was worried it might hurt the acidity. But in the end it just lowers acidity a bit, similar to tartaric stabilization,” she says.

In the end, they had more problems with bureaucracy than with winemaking. When they decided to submit the wine they had made in the egg to the Rías Baixas Concello Regulador, “they basically said, ‘Who do you think you are?’” Sonia recalls. After a drawn-out back and forth arguing that the wine wasn’t going to harm Rías Baixas’ reputation, they were given approval. Now, they have two eggs and produce around 2,000 L per year of ‘Calabobos’, which is fermented in stainless steel and then aged on its lees for 12 months in the concrete eggs.

For Sonia, concrete makes the wine more mineral and herbaceous, and it takes less time to become rounder and creamier. After it became clear the wine was going to turn out fine, they turned to the question of what would happen in the bottle. Sonia says the bottle evolution is “fantastic, even when we bottle after a year and a half. The effect is similar to a foudre, but this wine always stays creamier, fresher, more fruity.”

Chestnut

Elsewhere in Rías Baixas, Eulogio Pomares has been revisiting conventional wisdom when it comes to aging materials for his self-titled project, separate from his family winery, Zárate.

Eulogio says that a shared pursuit of purity among winemakers in Rías Baixas is making some reconsider what materials best showcase Albariño as a variety. Although oak foudres have made their way into some top producers’ cellars in the past couple of decades, Eulogio isn’t totally convinced. “Used oak might not add anything, but it takes something away,” he says. “It intervenes as far as vinification is concerned and in the character of the wines.”

He says the choice of vessel should match the grape variety: Albariño benefits from oxygen, and if it’s kept in an overly protective environment and pushed toward a very primary style, the result isn’t very interesting. But with gentle exposure to oxygen, Albariño can develop more complex aromas and make wines that age better and longer.

With this in mind, Eulogio has been focusing on chestnut for the red and white Eulogio Pomares wines, called ‘Carralcoba’. He says chestnut interests him in part because of its potential for gentle oxidation and in part because of its historical significance. “I keep working with it because it has this local, artisanal origin,” he explains. “Before the arrival of stainless steel, winemakers used whatever was available in their area. Some people still do: in Bairrada, Luis Pato uses chestnut from the carpenter in his village, and in northern Italy they use chestnut as well.”

Eulogio Pomares. Photo by Indigo WineNearby, Nanclares y Prieto are also playing with chestnut in their winemaking. Their Albariño cuvée ‘O Bocoi Vello de Silvia’ (Silvia’s Old Bocoi) is aged in a single, 1,800-liter 90-year-old chestnut barrel, called a bocoi, that came from a local woman’s family. “It had gone two or three years without wine in it when we got it, so we decided to put white wine in first, since we have more of it to spare,” says Silvia. They were so pleased with the result that they decided to release a white wine that centers the bocoi and its history.

They couldn’t find more chestnut in Galicia, so they sourced barrels from different cooperages until they found a profile they liked. These became the barrels used for ‘A Graña’, and Silvia says the initial result was “spectacular.”

“It’s very clear that chestnut accentuates Albariño and gives it power,” she says. “Chestnut gives it oxygen and highlights the variety without adding strong oak aromas. It’s much more subtle. There aren’t so many notes of vanilla or spice like you get with oak.”

Chestnut barrels at Nanclares y Prieto. Photo courtesy Silvia Prieto.Chestnut isn’t only a part of Rías Baixas’ history; it’s the material that most shaped traditional winemaking in every region of Galicia. Although there are native oak trees in Galicia, their wood was never really used for more than kindling. Chestnut was much more valuable: its strong, long-lasting wood was used for everything from beams in houses to barrels for wine, and chestnuts were the main source of carbohydrates in the Galician diet before the arrival of the potato.

For Diego Collarte of Cume do Avia, in Ribeiro, chestnut is more than just another material. “It’s the only material we want to use,” he says.

R-L: Diego, Álvaro, and Fito“ Our wines could be technically ‘better,’ more polished, more rounded in Austrian foudres, but they’d stop being a little bit Ribeiro. If we’re talking about geography, geology, climate, and Ribeiro’s grape varieties, then we also have to be consistent with the materials we use.”

Diego explains that Cume do Avia (made up of Diego, his brother Álvaro, and their cousins Fito and Anxo) originally made their first vintages in 2013-2015 in a more conventional way, with the help of an enologist. But in 2015, while making a wine with Alberto Nanclares and Adrián Gutierrez of Vinoteca Bagos in Pontevedra, they had the idea of using chestnut. Since then, Diego says, they’ve never abandoned it. After beginning with one old barrel and a rented winery space, they were able to begin collecting and recovering old chestnut barrels, upgrading them for modern winemaking with metal taps, manholes, and top doors. The largest is 4,300 liters, and the smallest is 1,400 liters.

“It didn’t seem like a decision we had to make; it felt like a decision that was already made, just like using indigenous varieties,” Diego says. “Now everyone understands it. Fifteen years ago, though, you had to explain why you wanted to recover native varieties—to get poetic, it’s because you’re bottling the landscape and territory. And if that applies to the vine, it should also apply to the other materials you use in the winery.”

Cume do Avia’s chestnut barrels. Photo courtesy Diego Collarte.Diego agrees that chestnut is more oxidative and wines evolve sooner, and says it also gives wines a bitterness that works to integrate the high acidity in Galician wines. “There’s wisdom behind ancestral practices,” he says.

That’s not to say other materials aren’t perfectly viable. “Our wines could be technically ‘better,’ more polished, more rounded in Austrian foudres,” he says, “but they’d stop being a little bit Ribeiro. If we’re talking about geography, geology, climate, and Ribeiro’s grape varieties, then we also have to be consistent with the materials we use.”

That’s also why, he says, whites and reds from Cume do Avia are almost interchangeable. “In a stone lagar [wine press], whites and reds are processed almost the same. All our wines have stems, both whites and reds. Reds are lightly extracted, because in a lagar you can’t extract for long without problems. So the fact that stone lagares were used everywhere shapes the wine profile.”

A traditional stone lagar in Moaña, published in “O Viño” (1993, Ir Indo Ediciones)Granite

In Ribeira Sacra, at Familia Seoane Novelle (formerly known as Prádio), a mix of “romanticism, nostalgia, and respect for what was always done,” sent Xabi Seoane in search of modern-day stone lagares to ferment his wines.

“I wanted to connect with and add value to what our land, our region, and our history represents,” Xabi explains. “And our history tells us that in the Middle Ages there were outdoor granite lagares found all over Galicia, next to monasteries, rectories, and the manor houses of the nobility. And then, this entire system disappeared. It’s been preserved a bit in northern Portugal and in the odd house around Galicia, but basically the whole thing disappeared.”

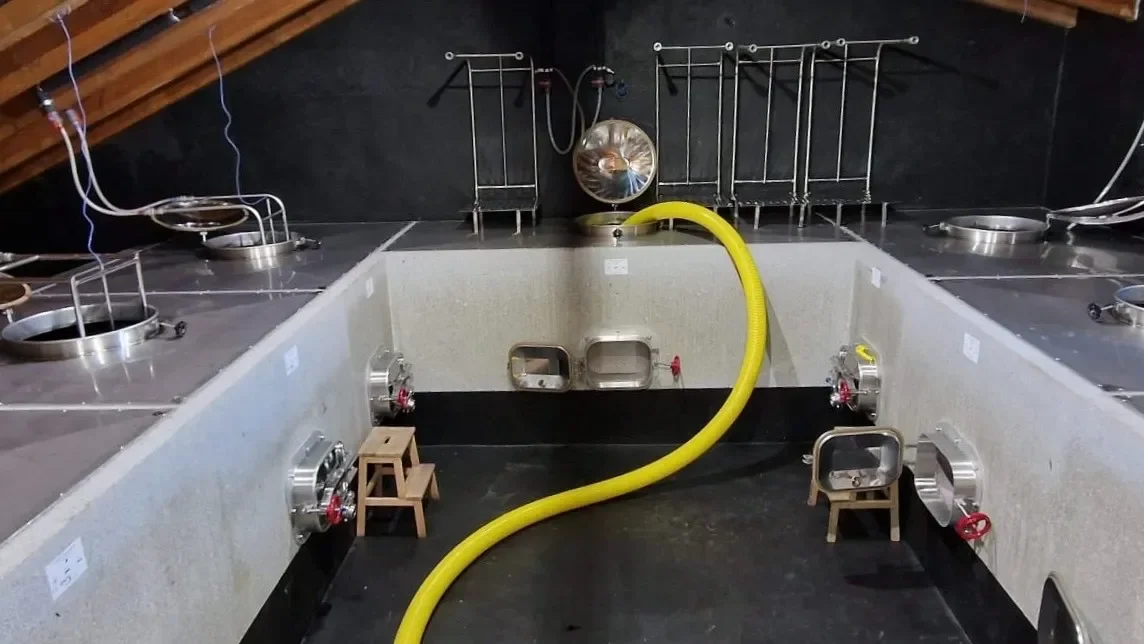

After Xabi took over the family winery, he began the search to find someone who could make a modern version of the historic lagares that he had in mind. Nearly every quarry he spoke to said it would be too difficult. After speaking with “practically all the sawmills and quarries in Galicia,” he says, he found Ánforum, a company dedicated to making special granite pieces. They agreed to take on the project, and Xabi worked with them to design the lagares. The final product is what’s in use today: three 3,000-liter and six 2,000-liter tanks, fitted with stainless steel manholes and wide lids for punchdowns.

Xabi’s granite tanksAfter years of working with the lagares, Xabi says that their value is more in the link with tradition and the land than anything granite adds to the wines. “Granite controls temperature very well, which is good for fermentation and maceration, but it doesn’t contribute anything else,” he says. “It’s a reductive environment, in the same way that stainless steel doesn’t oxygenate wine.“ He ferments all his red wines in the granite lagares, then leaves them to macerate with the skins for close to three months. Once fermentation is finished, he racks them into barrels. To “close the whole cycle of local materials,” Xabi is working with a local sawmill in Lugo and a Basque cooperage to make barrels from local chestnut.

An action shot of Xabi in the wineryThe Future

Will these winemaking vessels become part of tradition? Will more producers jump on the alternative materials train, and will Galicia’s DOs—or consumers—ever be convinced? These winemakers aren’t so concerned. For them, it’s more about the freedom to experiment, express the land, and make wines that feel true to themselves.

“At a regional level, I think all winemakers who love this profession need research and curiosity,” says Silvia. “So what if you do part of your winemaking in new vessels, or try things—who is anyone to say that it can’t be done?”

For Sonia, using different materials is an opportunity for consumers, not an obstacle. “It’s important to do new things,” she says. “We know young wine is what sells in Rías Baixas, but it’s important to step out of the box of young, fresh, fruity wine. If you mix different parcels, stainless steel, barrels, cement, you might get something exceptional, but you won’t identify what each thing contributes, so it’s good to try and learn. It’s great to give consumers the same variety in different forms: as a young wine, aged in stainless steel, aged in wood, on its skins, sparkling... that way they can really see what each method brings.”

Diego feels like the market is finally coming around. “There’s been a lot of resistance, but I’ve noticed much more openness now,” he says. “People now seem to be looking for freshness. When we started, the kind of wines we made weren’t the trend. It’s a tough moment, but at least our identity aligns with market evolution, even if we’re not benefiting yet. It’s a long-distance race.”

“In the end, if you make wine with feeling, you may succeed or you may not,” says Silvia, “but you’ll transmit it to your clients, to the world, to people, with much more passion. As long as there’s respect and quality, trying something new is a good thing.”