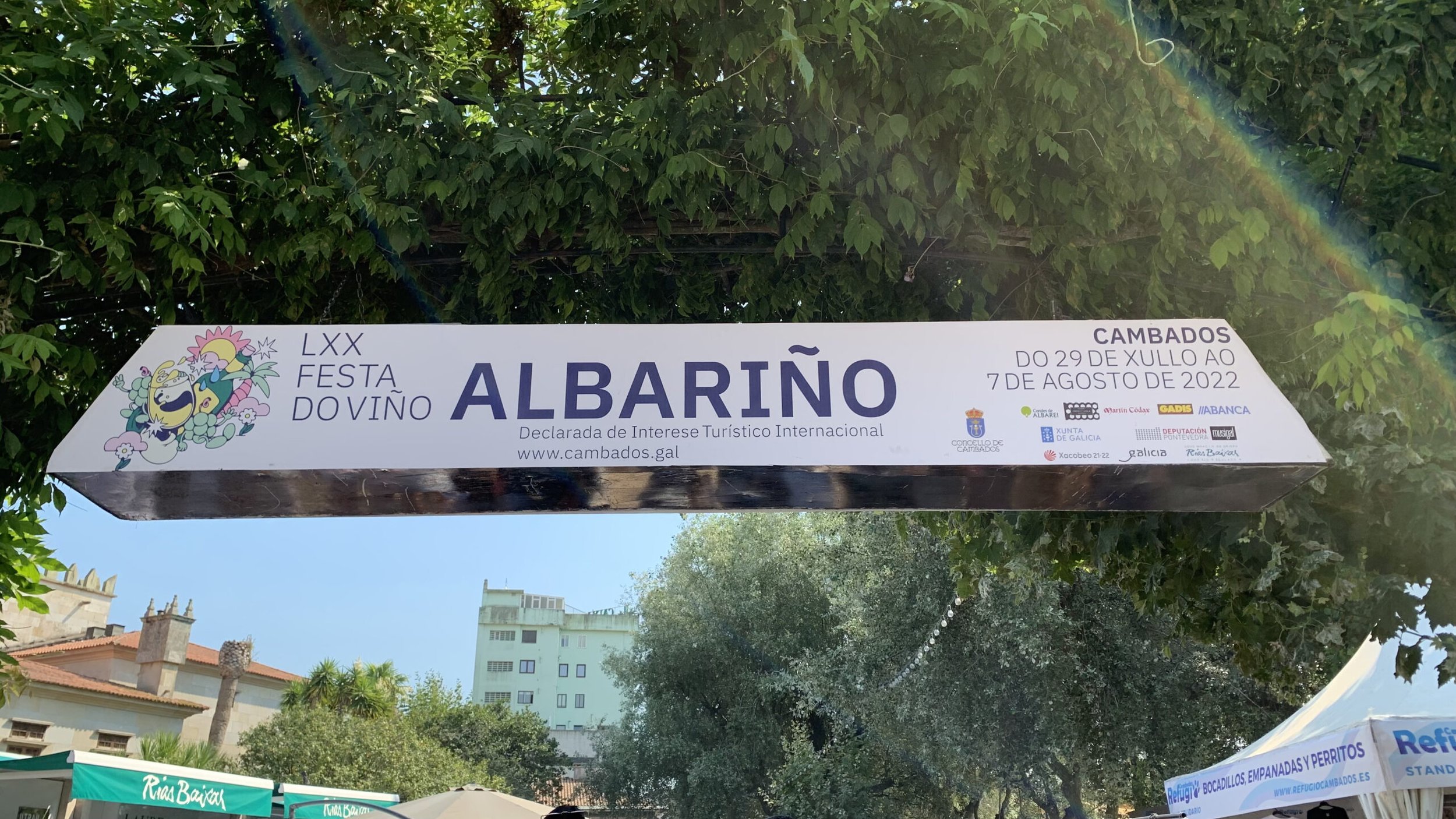

Albariño Day: How the Rías Baixas’ Biggest Party Got Started

Every year at the end of July, the streets of Cambados fill with revelers sporting wine glasses hanging around their necks, all eager to celebrate the Festa Internacional do Albariño: the “International Albariño Festival.”

The rest of the world just celebrates one Albariño Day to honor the Galician grape, but here in Rías Baixas the party goes for a whole week. Like most popular Galician parties, it’s an all-you-can-eat-and-drink-without-bursting marathon, complete with concerts, fireworks, and maybe the occasional full-frontal nudity.

The Festa is partially responsible for making Albariño from Rías Baixas world-famous, but most people don’t even know it exists. So what is this party, and how did it get started?

Bernardo Quintanilla

The year was 1953, and Bernardino Quintanilla was feeling cocky. When he wasn’t practicing law in neighboring Vigo, Quintanilla tended a small vineyard of albariño which produced a handful of bottles. He shared his wine with a circle of intellectuals, politicians, landowners, and other prominent men. Quintanilla’s circle of friends included Ernesto Zárate, a local landowner and fellow winemaker with considerably more experience growing Albariño in the Salnés Valley.

Over dinner one night, Quintanilla and a few friends debated a common question in the local taverns at the time: who made the best Albariño? Amid the banter, Quintanilla started thinking. Why shouldn’t his wine be better than the rest? Was it really out of the question that his plot made the best Albariño?

There weren’t that many growers, so it wouldn’t be too hard to make a judgement. There was one problem, though. Subjective tastes, falling prey to outside influences, would make it difficult to determine a definitive winner. Quintanilla came up with a plan. Not long after that fateful dinner, he challenged Ernesto Zárate to a vinous duel. Nine wines, tasted blind by a panel of growers and respected gourmands. The winner would be crowned the best Albariño in Cambados. Zárate, never one to back away from a friendly joust, accepted the challenge.

The first ever Concurso do Albariño took place the night of August 28, 1953. Quintanilla, Zárate, and seven other growers from a select circle of mutual acquaintances presented their wines at a dinner held in a friend’s garden.

And what a dinner it was.

In the kitchen was Pepita, Quintanilla’s sister. On the menu? Twenty-eight kilos of lobster, six chickens, and heaps and heaps of crabs. The pioneering Albariño-lovers washed it all down with nine bottles of champagne, thirty-two liters of local red wine, six bottles of water, cognac, anise, and of course, Albariño. And how much did this bacchanal cost? In total, the bill for the festivities was 4,389 pesetas, or about 1,800 euros in today’s money. Even from the beginning, the Festa had financial help: 750 pesetas from the Town Council of Cambados and another 250 pesetas from the provincial government. The rest of the sum was charged at the door: 60 pesetas a head. Just a bit less than the €400,000 the city council shells out today.

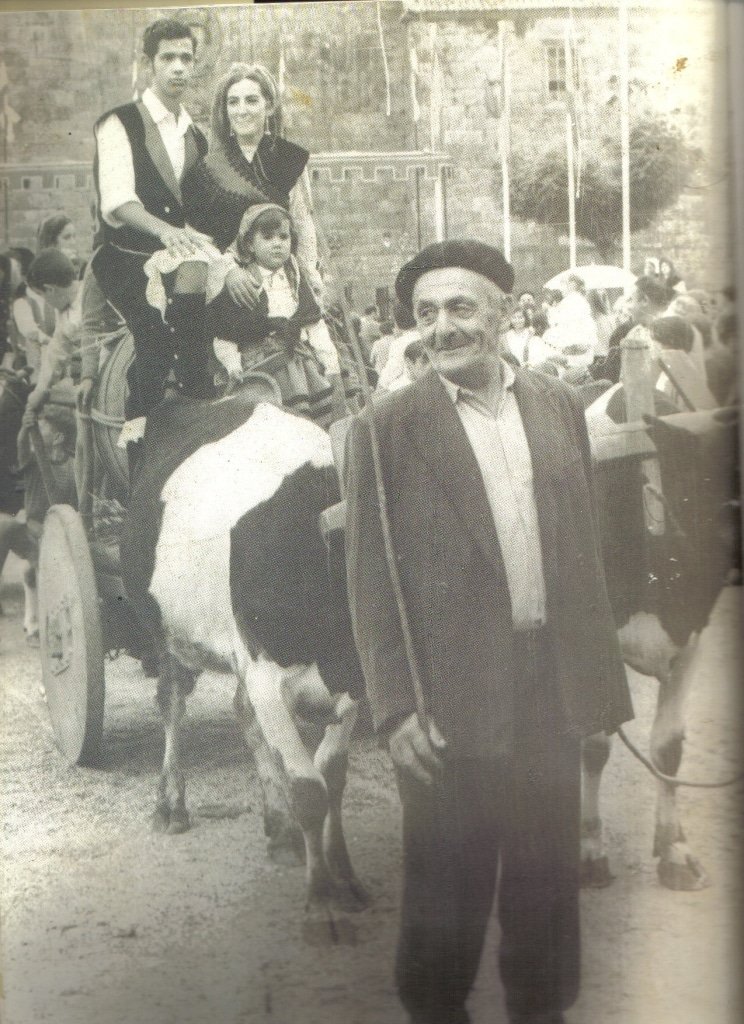

José Rodiño

After appetites were sated and taste buds fully warmed-up, the tasting began in earnest. Bottles hooded to conceal their identities were brought out, one after the other. The dinner guests concentrated, carefully analyzing each glass set before them and marking it with points based on its aromas and taste. They each turned in their votes and waited with anticipation for the final tally. When the dust settled, only one wine was left standing—and it didn’t belong to either Zárate or Quintanilla!

The winning entry came from José Rodiño, a farmer from the neighboring town of Carballal. Leading his team of oxen and cart to and from the town, always smartly dressed and sporting a boina, the black beret typical of Galician men of a certain age, Rodiño was no stranger to the taverns of Cambados. Though he was neither the owner of a pazo nor as wealthy as his competitors, in a lineup of wines without regard to the social standing of their creators, the underdog was the clear winner.

The unexpected champion of the first edition left Quintanilla and Zárate thirsty for a rematch. They held another competition the next year (Zárate won, and Quintanilla came in second place). News of the dinners spread, and the Cambados town government became involved in later editions. Word of the contest also reached the table of esteemed Galician gourmand and writer Álvaro Cunqueiro. Never one to miss an opportunity to drink wine, Cunqueiro and his friend and colleague Xosé Maria Castroviejo capitalized on the competition’s success and volunteered to become its official historians, chronicling each Albariño Day year after year. We can only assume they drank wine out of a sense of historic duty.

Ernesto Zárate (center) holds his winner's trophy while Quintanilla (2nd from left) looks on

By 1965, the contest was in its 13th year and had grown into a true festival. That year was the beginning of a sea change for Albariño—Franco’s Minister of Tourism, Manuel Fraga, came to town. A native son of Galicia, “Don Manuel” fell in love with what Cunqueiro called the “golden prince” of wines , and used his influence to spread the festival far beyond Galicia’s borders by featuring the Festa de Albariño on Spanish state television.

Fraga’s involvement didn’t stop there: in 1969 he became a founding member of the Capítulo Serenísimo do Viño Albariño. The “Serene Order of Albariño Wine” was formed as a way to lend an air of formality to the proceedings. Apart from Fraga, other founding members were Alvaro Cunqueiro—who had a talent for popping up anywhere he could have a continuing supply of good food and wine—and Manuel Cabanillas, brother of famous Galician poet Ramon Cabanillas.

Over the years, the Capítulo Serenísimo also attracted attention to the festival by inducting celebrities, singers, and politicians like Charles de Gaulle (class of 1970), exiled president of Argentina Juan Perón, and future king of Spain Felipe (class of 1998). In 2002, Spanish president (and leader of Fraga’s conservative Partido Popular) José Maria Aznar was made a Knight of Albariño, later followed by his successor in the PP, Galician-born Mariano Rajoy.

Throughout the 1970s the festival grew to incorporate everything from a cycling championship to commemorative stamps and envelopes. In 1977, it was declared a Fiesta de Interés Turístico Nacional, joining the ranks of other Spanish celebrations that draw in tourists from all over the country. In 1981, the newly-approved Denominacion Específica de Albariño brought technical expertise to the proceedings by organizing seminars on modern production techniques. They also used the Festa as a springboard to organize the wine sector, building on growers’ interests in making their wineries more profitable. These efforts culminated in the first Albariño competition officially sponsored by the brand new Denominación de Origen Rías Baixas in 1988, featuring twenty stands for producers and an official booth for the Consello Regulador.

Not even the Festa do Albariño was immune to the political and social changes of the tumultuous post-Franco 1980’s. The Movida Viguesa—named for neighboring city Vigo—was an offshoot of the Movida Madrileña, a post-Franco social movement in Spain’s capital that tested the limits of the newfound freedoms brought by the dictator’s death. One part of the movida was a changing musical scene, best captured by punk rock bands like Os Resentidos and Siniestro Total—famous for their song “Miña Terra Galega” (sung to the tune of Sweet Home Alabama) and other hits like “I’m Gonna Dance on Your Grave.”

Concerts by these groups and others brought in crowds of young people and helped to attract a younger generation to the wine scene. The festival brought out its glamorous side in the ’90s, when Julio Iglesias became a Knight of Albariño and fashion designer Adolfo Dominguez provided new capes for the occasion. Women joined the Order of Albariño in the ’90s when the first president of the Rías Baixas Consello Regulador, Marisol Bueno, was made a Dame of Albariño.

The author wearing the traditional wine glass around his neck—nicely tied up so it won't get lost

Nowadays the solemnity and sobriety of the Serene Order coincide with the celebration and spectacle of a true Galician party, as the festival hosts musical performances and parades in a week-long marathon that attracts thousands of Albariño lovers. Wine glass-toting patrons throng rows of stands manned by winemakers pouring samples for the thirsty public, and a tasting competition still determines who gets the prize for the best Albariño.

When Zárate and Quintanilla met for a their first dinner in 1953, they never could have dreamed that their friendly competition could grow into one of the most important events for an entire wine appellation, and launch Rías Baixas to worldwide fame.